Space Age Pop from Maddalena Fagandini and…

I can’t remember who it was. It could have been… George Martin

Maddalena Fagandini – Alchemists of Sound (2003)

There are moments in a career when several things seem to come together at once and raise the profile of an artist. This was that moment for Maddalena Fagandini. In January the play Orpheus with a complete Radiophonic score and effects soundtrack was broadcast, in March her work underscored the Ideal Home Exhibition and now here she is making moves into the world of pop with one of the greatest producers of all time. Early 1962 was a peak for Maddalena and the first inkling that George Martin got about a beat group from Liverpool who would define the rest of his career.

Time Beat and Waltz in Orbit were the first Radiophonic Workshop music to make it out of BBC broadcasts and onto vinyl. The modest success they achieved at the time was not due to any lack of support from the BBC, EMI’s Parlophone Records or the press. Pop has a fickle and exacting standard for what makes a hit which this record didn’t meet. Nonetheless, its place in history is assured. It and the story behind Mr Cathode reveals much about the world it came from.

1951 – Guggle Glub Gurgle

The notion of taking an electronic rhythm track and making a pop hit from it was not new to George Martin. During his early days at Parlophone Records, he produced The White Suit Samba by Jack Parnell And His Rhythm. This song was credited as Incorporating Mary Habberfield’s “Guggle Glub Gurgle” from the soundtrack to Ealing Studios Film “The Man In The White Suit”.

Habberfield’s pioneering sound effect was made in 1951, before the widespread use of magnetic tape and is an absolute landmark in sound design and musique concrete in the service of a soundtrack. Mary Habberfield left sound editing behind, but her legacy was assured by this incredible chemistry lab samba1. She was asked to create this zany rhythmic effect during the film’s production so that the he film’s composer Benjamin Frankel could work it into his score. It’s this pair – Frankel and Habberfield – who first fused the concrete with the conventional.

1952 – The White Suit Samba

In 1952 Jack Parnell and George Martin jazzed up the gurgling sound effect – which had been released as a sound effects disc – and added daft chemistry punning lyrics from T.E.B Clarke. It was a modest hit and made its way to the USA too. Roll on to 1960 and it’s not surprising that the appearance of electronic beats on his TV caught Martin’s ear.

October 1960

As covered previously – http://rws.bbcrecords.co.uk/staff/maddalena-fagandini/3rd-october-1960-music-for-party-political-conferences-broadcast-bbc-tv/ – Maddalena Fagandini had provided some musical rhythms for the party conference specials, broadcast late at night on BBC tv. The same Music for Party Political Conferences piece had then been used by the BBC Presentation department to accompany the BBC clock, between programmes.

Watching at home was George Martin. Newspaper articles from the time of release refer to this incident and the improbability of finding inspiration whilst watching “…believe it or not, a Party Political Broadcast2.” You can imagine him wandering over to a nearby piano and picking out a tune to accompany the interval signal though.

Martin was an innovator in the studio and a maverick producer of pop music. His attraction for the Beatles was in part that he could navigate the recording process and technology into uncharted waters. He was also an innovator in the music business. No one else was releasing comedy records and theme music like Parlophone under his management. There was also jazz, light classical, exotica, world music and novelties that straddle all genres. He was on the lookout for new sounds wherever they appeared and was very keen to break into the pop market in a bigger way than had been possible for his motley assortment of Scots, Goons and band leaders thus far3.

What Martin did next is only recorded in fragments. In Alchemists of Sound, in a section titled The Enigma of Ray Cathode, Desmond Briscoe recalls a conversation he had with a “gramophone company producer” and no doubt they had much to discuss. Martin also talks of visiting the workshop, although at the time of releasing the Ray Cathode record it was already “some time ago…4“.

January 1961 – BBC Television Theme Number 1

By January Rex Moorfoot, head of BBC Presentation and the man responsible for smartening up the space between programmes, was involved. The resulting piece was to be titled BBC Television Theme no.1, with the idea of more to follow5.

April 1961 – Tune In Time

Martin was still working things and a few months later and ever “impelled by the pop-music market’s ceaseless quest for something new” [he] “arranged to get the recording rights from the BBC6“. This was accomplished with the help of music publishers Robbins Music7. The BBC tv theme idea faltered though, and after acquiring the rights the name Tune In Time was adopted for the project.

July 1961 – Tunin’ Time

And by July, Tunin’ Time was the chosen name. Then a large chunk of time goes missing before the record comes out. There is a similar gap in Maddalena’s CV at the Workshop, which may simply be a lack of attribution in the tape archive or perhaps another secondment had come to an end and she was in rotation. She’s there in the second half of 1960 but not visible in 1961 until October.

At some point, the B-side contribution is realised at the Workshop. According to one account this “was born after a visit George Martin paid to the BBC’s Radiophonics Department.”8 How long after is hard to say.

Intriguingly there may have been more than two tracks in the offing. As already mentioned, the BBC were keen on having Television Theme 2, 3 and so on. And, according to the news reports, George Martin was furnished with “two long tapes of assorted electronic noises”9. Included was a 5/4 rhythm made from “a tap dripping on a pail reversed and cut up.” which Martin likens to Dave Brubeck’s Take Five. The 1959 hit is the biggest-selling jazz song of all time and by far the most famous 5/4 song to boot. Whatever else did or didn’t happen with those tapes nothing more than the two Ray Cathode pieces came out of this collaboration10.

25th January 1962 – A Star Is Born? (Daily Herald)

After more than a year of whatever was taking so long, Ray Cathode was announced to the public in The Daily Herald. Under the headline Odd Place For A Star To Be Born.. Henry Fielding previews “a bouncy, slightly unearthly little tune called Tunin’ Time …from the BBC Radiophonics Laboratory (sic)11.” Maddalena and Desmond Briscoe are mentioned with Mad’ getting credit for the rhythm. As well as that working title for Time Beat, there is no mention of Waltz in Orbit.

This is quite early to be promoting the single and it may have been somewhat premature. The gentlemen of the press seem to have been invited to the Workshop despite the single not being in shops until “about March or April”. Also, Martin says

“we’ve sent the Radiophonics people some records by The Shadows so that they can pick up the sort of thing we want”

George Martin in The Daily Herald – 25th January 1962

That line could indicate that the melody from Waltz In Orbit had been delivered and they were awaiting the tape.

1st February 1962 – Unenthused

Also visiting the Maida Vale ‘laboratory’ ahead of release were Patrick Doncaster and a photographer from the Daily Mirror, who held back their story till the day after release. In a BBC memo, it was noted that no photos were taken nor “any particular enthusiasm for the Workshop” shown. Oh dear! Had they even heard the finished Ray Cathode “concoction12” at this point though…?

21st February 1962 – Recording date?

Given the promotional push in January and some of the comments in the Daily Herald article, it might be reasonable to assume that both sides were finished at this time and simply waiting for a slot in the busy Parlophone/EMI release schedule. Instead, the recording session seems to have been on this day13. The recording took place at EMI Studios on Abbey Road. EMI Number 2, to be precise. A studio of incomparable importance in recording history and hallowed ground in popular music.

There are several possibilities which explain this: By January there was a demo tape version, played to invited press; Ony the Time Beat had been recorded and this date is for Waltz in Orbit only; Nothing had been recorded and the press were being told in January about what was coming soon, with nothing at all recorded.

The latter seems unlikely – Martin’s comment about the Shadows records excepted, and that might tie in with Waltz in Orbit. That track was a matter of Maddalena Fagandini providing a top-line to go with an instrumental piece and The Shadows’ chart-topping sound was the in-thing at that very moment.

It’s probably worth explaining the process here too. Time Beat was built from the rhythm track up, of course. All the band needed was the Radiophonics tape playing in their earphones, or that of the conductor. In the studio control room, the engineers would be missing the sound of the band with the Radiophonic tape and recording the result onto another tape machine. This tape-to-tape process was common at the time, allowing vocalists to come in and record on top of a pre-recorded backing, which allowed them to try a few takes. Multitrack tape machines were around too, but not as common at this point.

As for Waltz In Orbit, it’s possible to misunderstand how this was done. It’s sometimes said that for this piece Martin sent the backing track to the Workshop and Maddalena put the Radiophonics on top. Can this be how it was done though14? More likely, and in line with the recording dates, is that Martin handed a score to Maddelena who created a single 4-bar phrase which was then looped. A careful listen to the finished piece confirms that this top-line never skips a bar and comes back in on regular 4-bar intervals. The band could play along, as with Time Beat, as the engineers mixed and recorded it.

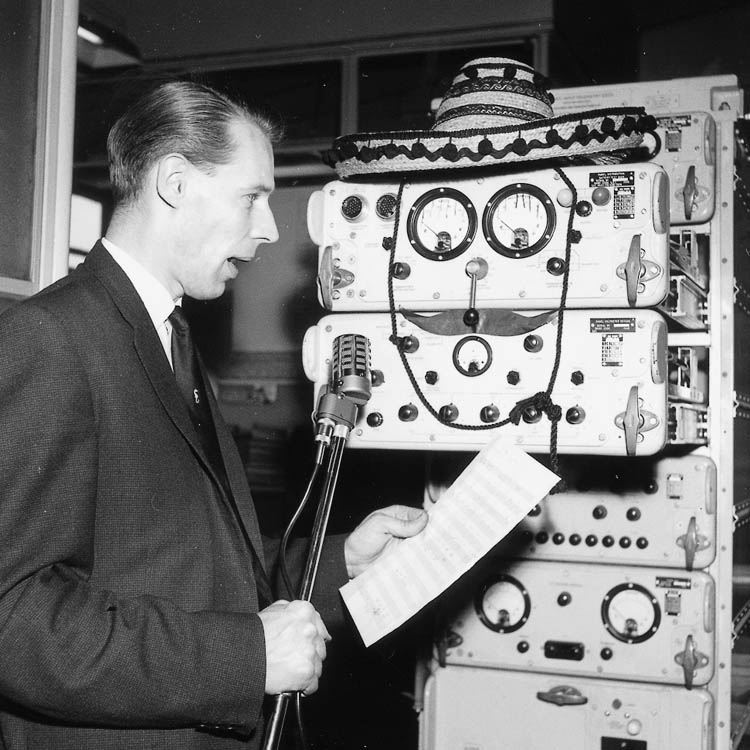

March 1962 – Photoshoot

Ahead of the release date, promotional copies of the disc were pressed up and presumably distributed to the tastemakers and broadcasters of the time. There was plenty of time to do this following the recording date.

Also pre-release, George Martin posed for promotional photos. These may also have been taken with a view to inclusion on a picture sleeve, which was never printed15. As you can see, Martin is pictured with a microphone held up to Ray, presumably trying to capture the sounds emitted by the Ray Cathode. He also seems to be in the act of inserting a record into Ray’s electronic brain. Or is he trying to remove it? Meanwhile, we see that Ray is wearing a sombrero and (fake) moustache in the style of a Mexican bandito16. This fits with the vaguely Latin American feel of Time Beat and Waltz in Orbit.

The equipment posing as Ray Cathode here – complete with eyelashes! – is not identified. It’s certainly high-end stuff in a 19″ rack with a drawer system to aid servicing. It does not appear to be a computer,17 although it might be part of EMI’s EMIDEC 11018, which was the UK’s first all-transistorised programmable computer19.

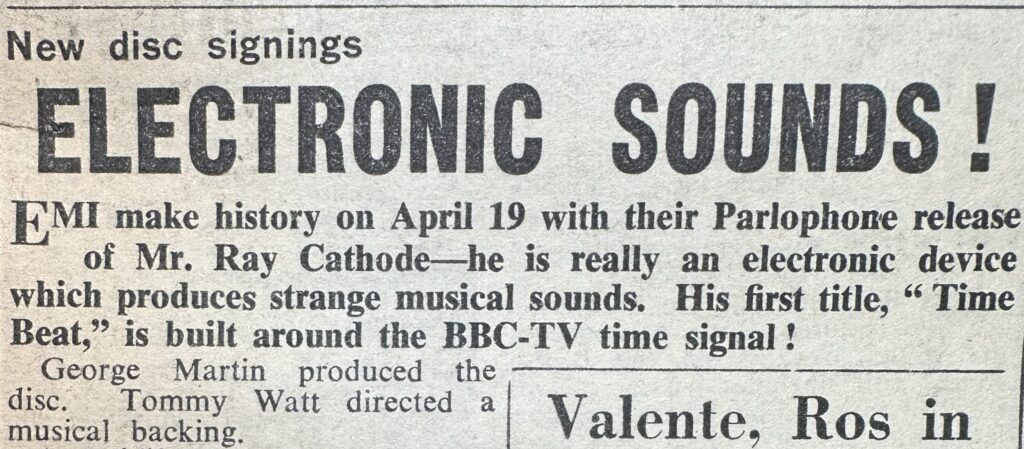

6th April 1962 – Electronic Sounds (New Musical Express)

The New Musical Express are the first of the music press to herald the imminent release of the Ray Cathode record. This snippet is part of the New disc signings column which is an opportunity to take the spiel from Parlophone at face value and introduce mister Ray Cathode. And then they undercut the mystery slightly with the more revealing tidbit that Tommy Watt was the musical director.

Tommy Watt

Tommy Watt was a top-rank big band leader, composer and arranger. He was signed to Parlophone and released two George Martin-produced albums and a bunch of singles with them in the late fifties. He also lent his skills to several Parlophone releases in the early sixties, including Morse Code Melody by The Alberts just a month after the Ray Cathode session. You might also know that he was the father of Ben Watt of Everything But The Girl20. Tommy Watt turned down the chance to work on arrangements for the Beatles, but then a lot of people missed their chance with that particular group. Tommy Watt was a jazz man through and through though and not bothered by that. He eventually preferred to quit music and take up interior decoration when paying work for his preferred style dried up altogether in the early seventies. This pop gig was probably just a job to him too.

Tommy Watt’s role in Ray Cathode is limited to a jobbing arranger, conductor and probably session musician. He was a very accomplished pianist and George Martin almost certainly left that to him. There’s no information on the other players, but Watt was reportedly very particular about who he played with. Martin evidently had a high opinion of Watt. The Beatles offer and other jobs like Ray Cathode indicate as much. Tommy Watt had little interest in any music that wasn’t in the arena of his beloved big bands.

There are more mentions of Watt. In The Stage a few months later it is confidently stated that “Tommy is the musician behind the current Parlophone release, ‘Time Beat’ which is now getting many broadcasts”21. At that time he was running two big bands and working with Brian Rix on TV22 and stage shows. Second, the original BBC Radiophonic Workshop – 21 album documents are even more explicit about his role in Ray Cathode. The composers are listed as “Maddalena Fagandini/Tommy Watt”. It has to be said that this is probably a mistake as other sources are clearer that George Martin wrote the musical parts23. The track is further annotated: “Instrumental version orchestrated by Tommy Watt – produced by George Martin for Parlophone Records.” As this early draft of the tracklist was not taken forward we’ll never know how this would have been revised before releasing the album24.

So, we have a third person behind the Ray Cathode curtain. Although his role was not a secret at the time it as been rather lost to memory since the odd mention in the press. The very positive Stage article was, in between the lines, a sign of a difficult road ahead for Watt. He’d not made a success of leading the prestigious BBC Northern Dance Orchestra and although he’d formed another band for private engagements and a Trades Union Congress sponsored festival circuit was in the offing as well as his work for Brian Rix this was the last hurrah. Although he may not have minded the lack of credit on the disc, he certainly wanted the business to know that he’d had a hand in the making of Ray Cathode and could be called on for more.

12th April 1962 – It Aint Human ..but sounds a treat (Daily Mirror)

The Daily Mirror may have held back their article but they were right on time publishing it with the release just one week away.

Patrick Doncaster signs off his review with the comment “…you will have a tough job finding out who is playing what”. He’s not wrong there. As he points out the writing credit is simply ‘B.B.C Radiophonics’.

Ray Cathode25 is a cover name. In part this was a necessity. The record was a project, not a career opening. Maddalena Fagandini’s musical instincts were not (probably) to make more pop music.George Martin was running a major record label as well as trying his hand at composing.

Much has been and will continue to be made about the lack of composer credits on early RWS works. George Martin is the co-writer of both pieces with Maddalena responsible for the original Time Beat Rhythm. Although neither gets direct credit, Martin is taking less than his share here though, as the only real name points to the RWS. Tommy Watt and his unknown session musicians are even less acknowledged.

Martin did get his key collaborators’ names out into print though. There was no serious attempt to obscure the ownership.

13th April 1962 – Ray Is Out of This World (Leicester Evening Mercury)

Alan Goddard wrote an article syndicated out for many regional newspapers under different headlines over the next week or two. He seems to have visited George Martin at his office and got many of the details.directly from the man himself. This included the tantalising prospect of other Radiophonic productions.

Weirdly he prophesied the next two singles which the RWS were involved in over a year later whilst referring to a tape of “assorted electronic noises” provided to George Martin by the RWS. This included “background sounds to TV programmes like documentaries on railways and the latest science fiction series”. This is completely inadvertent, but could be taken to mean Giants of Steam and Doctor Who.

14th April 1962 – Can Concrete Music Hit The Charts? (Disc)

It’s fascinating to see how the concept of musique concrete was very well understood at the time. The Daily Herald article gives a potted history of tape music and here in Disc it headlines their piece.

Electronic, or “concrete” music is not new in itself, but it is on pop discs “It is concrete music reinforced by musicians” said Martin “so we’re calling it reinforced concrete music!”

Disc 14th April 1962

Disc’s Peter Hammond quizzes Martin about the chances of chart success for an “electronic brain”. His answers reveal an interesting take on the record-buying public. Martin’s view is that they are “going for the music itself”. He explains that “They don’t necessarily buy names or words any more.” This is perceptive given the pre-Mersey Beat era instrumental successes like Acker Bilk’s Stranger On The Shore. It bolsters the justification for hiding his own and other’s names from view too. No one involved was expecting to become a personality off the back of this and the instrumental hits he and others were having at this time do bear his theory out26. On the other hand, a couple of months later George Martin signed the Beatles to Parlophone Records and certain ‘names’ and their ‘words’ would be ‘gone for’ in a way never seen before or, arguably, since.

Elsewhere in Disc, Don Nicholls’s Disc Date review column gave Ray Cathode’s err, disc, four stars and further points for the very idea which “you could kick yourself for not acting on first.27” Nicholls assesses that it is “very catchy”, and “both gimmicky and good”.

14th April 1962 – Ray Cathode Makes Pop History (Liverpool Echo)

Another pen name, Disker28, played up the angle of Time Beat’s mix of concrete and “normal orchestral instruments”. Although the history had been made already with The White Suit Samba, that was time out of mind for young pop fans. Disker is excited by the prospect opened up by this record though. He points out that vocalists have been backed up by “extremes” of novel instrumentation in the recent past in the battle to win attention. Despite the instrumental nature of Time Beat and Waltz in Orbit, he speculates that this might be the start of an electronic era in pop music. It may have been a sign of things to come, and it wasn’t to be the start of such a revolution of course, but this is a viewpoint much like Martin’s own. George Martin was trying to push things forward and find that edge over his competitors within EMI and over at Decca. The blending of electronics and vocal performers as heard on The White Suit Samba though, remained elusive for a while longer29.

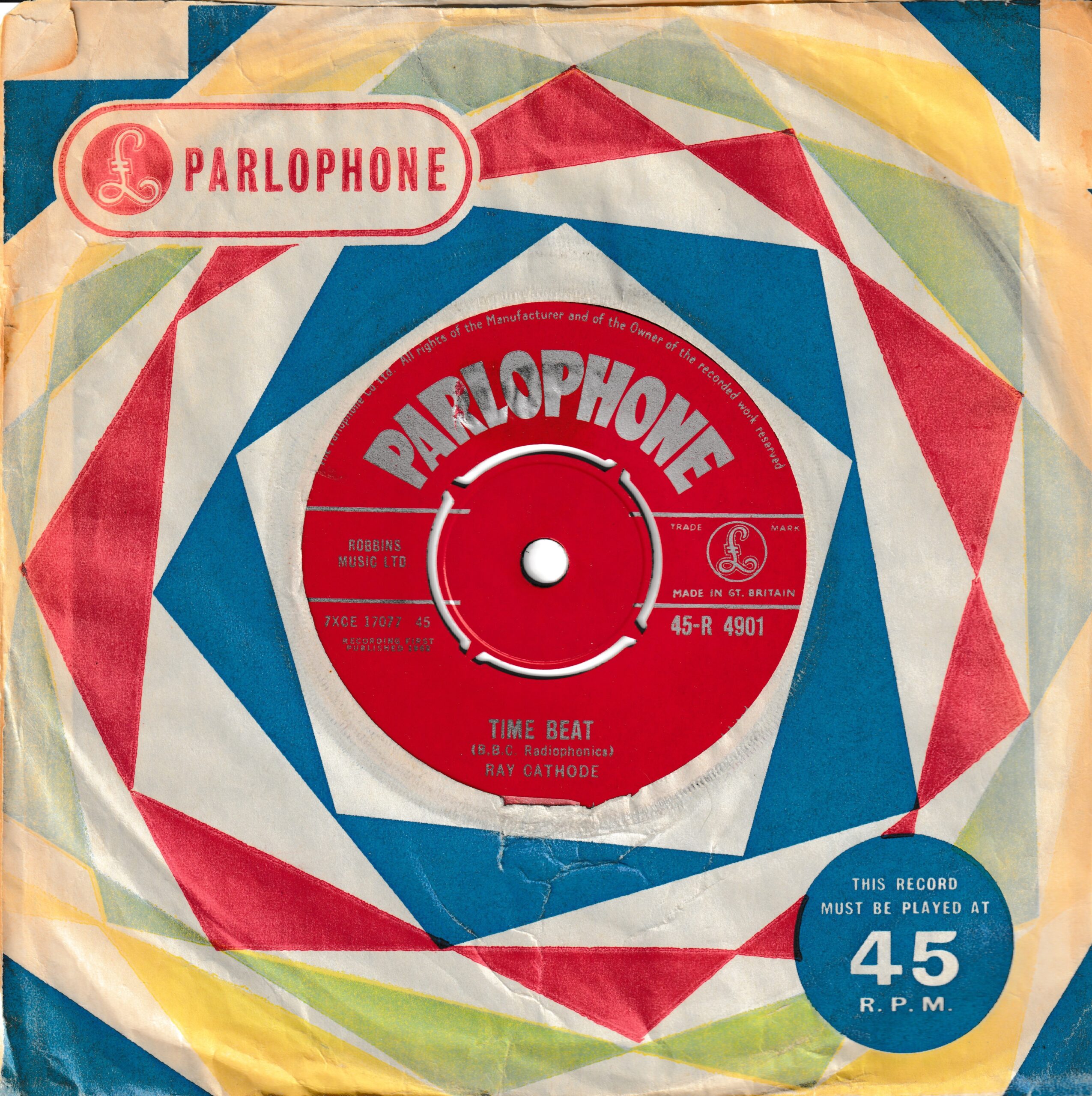

19th April 1962 – Ray Cathode – Timebeat b/w Waltz In Orbit released (Parlophone Records)

Time Beat b/w Waltz in Orbit was released by Parlophone Records on the 19th of April 1962 with the catalogue number 45-R 4901. The performer is the pseudonym Ray Cathode and the writer of both tracks is credited to B.B.C. Radiophonics.30

Time Beat begins with Maddalena’s rhythm track. Four measures of unadorned musique concrete. Then a piano. Single notes bounce up and then down a scale. An acoustic guitar strums along. Then what could be zither reinforces the piano melody before taking up a B section on its own. And so it goes with another variation to break things up.

Waltz in Orbit is in 3/4 time, of course. Maddalena provides a most beguiling melody with a sound that has a kind of springy resonance and like the best musique concrete can’t quite be pinned down in your mind whilst sounding familiar. Percussion comes from bongos and a thumb-rolled tamborine31. Syncopated piano chops and bass (guitar?) join in. The zither is back and occasional fill-ins from a xylophone.

A lot is going on with this record, and maybe that worked against it. We were told that Ray is a kind of AI that can write and produce music. On the other hand, it’s something from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop people. George Martin is the producer – even though he wrote it. You’ll recognise the beat on Time Beat from BBC interval signals but now it sounds more exotic – Spanish, or Mexican even. Waltz in Orbit is also European sounding with that zither, but also it’s space age! In the end, though the future of pop was not quirky, jazzy exotica with musique concrete seasoning.

Joe Meek had the right hit-making instincts32 with his ode to the Telstar communications satellite later in 1962. That international smash hit was backed up by the guitar-bass drums of Shadows rivals The Tornados. Meek and Martin probably followed each other’s developments in the studio and the charts with keen professional interest. You have to wonder if Martin heard Meek’s earlier experiments and Meek determined to nail the space-age pop template after identifying what Waltz in Orbit was lacking in chart appeal.

19th April 1962 – When The Robot Goes Pop (Manchester Evening News).

The tension between the Ray Cathode gimmick and the real people who created the record was further exposed in this article. Speaking to the Manchester Evening News George Martin explains who was actually responsible and then obfuscates.

This record is essentially the result of team work and close co-operation between the BBC, our own technicians and the musicians under the direction of Tommy Watt. But the ‘artist’ on the record, of course, is virtually an electronic brain guided by human hands.

George Martin quoted in the Manchetser Evening News 19th April 1962.

That last claim is more or less nonsense, of course. There are similar statements from George Martin littered around the newspaper articles as he tries to build a legend for Ray. “It just isn’t human”, is another misleading notion he puts about to create a daft character to front for the record.

21st April 1962 – Juke Box Jury (BBC tv)

Days after the record release Ray Cathode made his way onto the tube. David Jacobs was your regular host for another session of Juke Box Jury where a panel of celebrities passed judgement on a selection of the hottest new platters. This particular Saturday the judges were all singers Alma Cogan, Nina & Frederik and Neil Sedaka.

The verdict was that Time Beat was a MISS and this was borne out by the chart placings. In other words, it did not reach the charts at all33. That’s not to say it sunk without a trace. It was played extensively on the Light Programme apparently, rivalling other George Martin instrumental and comedy productions for air-time34.

https://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk/19d2ce6f3a2652e2ceff76d1d1413a94

April-May 1962 – Review Round-up

Further reviews dribbled in from the provinces, although they were not glowing. The MISS on JBJ seems to have marked a turn in opinion. The Birmingham Mercury’s John Gordon yawned through his piece grumbling that “music by machine – it had to come I suppose”35. The Seven Oaks Chronicle brings confusion to the narrative by claiming it was heard “as an introduction to children’s television”36. The South Western Star’s Record Review think there’s “something phoney about this sort of thing” although they reckon you should get it “for the record”37. A curio only, then. Finally, the Coventry Evening Telegraph goes in hard with the headline Like an Ordinary Organ. No, they are not impressed by the technical wizardry, although “the general sound is less obnoxious than I has expected” and they do admit to Time Beat having “a fine Latin beat38“.

Conclusion

In Alchemists of Sound, the narrative was that Ray Cathode had been forgotten the previous forty years. That is probably fair as the Radiophonic rediscovery bandwagon hadn’t really got going at that time. Many would surely have kept and treasured their copies though and Time Beat appeared on the 6-CD set Produced By George Martin 50 Years In Recording in 2001. No, it wasn’t a bit hit but you can easily get hold of a copy now for a reasonable sum so it must have sold a reasonable number at the time, possibly spread thinly over the months.

Maddalena Fagandini wasn’t destined to be at the forefront of reinforced concrete, as George Martin dubbed their fusion, for any longer than this single release. That is a great ‘what if?’ of Radiophonic history. Whatever delayed things for so long in 1961 may just have delayed the project too long for it to build momentum. As noted elsewhere Maddalena was in and out of the Workshop and that can’t have helped matters. And, to give Desmond Briscoe the last word it was just “a by-product” and a bit of fun” after all. But what fun!

- Bubbling Musical appears on the BBC Records album Off Beat Sound Effects – REC 198, 1975 ↩︎

- In The Groove by Alan Goddard – syndicated column in various newspapers including Ray Is Out Of This World in The Leicester Echo, 13th April 1962. ↩︎

- Adam Faith being an exception at Parlophone. ↩︎

- Can Concrete Music Hit The Charts? – Disc, 14th April 1962 ↩︎

- In 1967 Martin wrote and produced Theme One for the launch of BBC’s Radios 1 and 2. Whether the numbering was an oblique reference to the early TV theme idea or not I cannot say. It does seem unlikely, although the ‘One’ here doesn’t quite work for Radio 2, does it? ↩︎

- Odd place for a star to be born.. – Daily Herald, 25th January 1962 ↩︎

- Robbins Music was an American outfit with offices in London. The deal was probably done by Alan Holmes. ↩︎

- South Western Star – Record Review Around The Table 27th April 1962 ↩︎

- Alan Goddard piece again. He seems to have interviewed George Martin at his office. ↩︎

- I will speculate here that the combination of difficulties with publishing rights and Maddalena’s peripatetic BBC career put the kibosh on more Ray Cathode. In any case, the extremely limited sales in the event probably killed off any chance of a career. ↩︎

- He goes on to illustrate the work of the “engineers” who “record say one or two notes from a piano – or perhaps the sound of tinkling glass – and then they ‘manipulate’ the sound…” He is describing the sounds made by Maddalena for Orpheus which would have been in preparation at the same time as this article. ↩︎

- Maddalena Fagandini’s description from – Alchemists of Sound ↩︎

- The fact was gleaned from The Beatles – All These Years – Extended Special Edition: Volume 1 Tune In – Book 2 (phew!) by Mark Lewisohn. I have no reason to suppose this is an error and the dates are consistent with the release date. Still, it is strange how this timeline plays out. To be clear, both sides of the disc are quoted in Lewisohn’s footnotes as being recorded on this date. ↩︎

- If it was I think it would be unique because the problem is timing. For this to have any chance of working the band would have to play to a strict metronome, ideally from a tape prepared by the Workshop. Maddalena would then know the exact timing and could create a tape loop that would sync with the band’s recording. This seems like a faff with room for error and why I don’t think it’s likely. ↩︎

- The two photos in higher quality were taken from 45Cat, posted by Bam-Caruso on 29th Oct 2012. The “possible EP picture sleeve” claim is from the comments. ↩︎

- A hint here of Bandito The Bongo Artist by the American composer and inventor Raymond Scott, (see Manhattan Research Inc. Volume 2 – Basta, 2001) although it seems unlikely that Martin was borrowing this whimsical title. Scott’s piece was an advertising jingle, and only titled thusly in recording notes. Unlike the UK pioneers, Scott was actually developing equipment that not only played by itself but could indeed improvise – the Electronium. It’s more possible that Martin had heard of Scott’s work or more generally the idea of a machine ‘composing’ music. ↩︎

- Throughout the Ray Cathode publicity campaign, George Martin and the journalists refer to Ray as variously an “electronic brain”. Sometimes “guided by human hands”. Patrick Doncaster in the Daily Mirror describes Ray as “a mass of valves dials and wires” ↩︎

- According to Mark Lewisohn, this is what it is. I have to say I could not see this rack gear in any of the photos of the computer available and it looks decidedly analogue, not digital. ↩︎

- Another inspiration for George Martin’s creation could have been Max Mathews. Working at Bell Laboratories in the USA, Mathews arranged Daisy Bell (Bicycle Made For Two) using his MUSIC software – the first music computer program – in 1961. This is the kind of thing that might not have come to George Martin’s attention but could have been passed on by Desmond Briscoe and Maddalena. ↩︎

- Ben Watt’s memoir of his parent’s lives, dotage and his struggle to care for them Romany and Tom provides most of his father’s biographical details. ↩︎

- Tommy Watt’s Two Band – The Stage, 14th June 1962. ↩︎

- Dial Rix, which the RWS also contributed something to (TRW 4032). All wiped, of course, and no hint that Tommy Watt reunited with the RWS here. ↩︎

- The same kind of ambiguity exists in their attribution for Doctor Who ‘by‘ “Ron Grainer/Delia Derbyshire.” Yes, Ron thought Delia should have got due credit as a co-composer, but the score was by Ron and the arrangement (or realisation) by Delia, and that’s how matters remain. ↩︎

- BBC WRAC R125/742/1 ↩︎

- For those who have only known the flat screen, or never thought twice about the technology behind their bulky twentieth-century predecessors, the cathode ray tube was what made televisions and any other visual displays at the time work. The ray was a beam of electrons formed from a negatively charged electrode – termed a cathode – and directed inside a vacuum tube to the inside of the screen. The pun barely needed mention at the time, so ubiquitous was the term, although it’s now passing out of use and I doubt that its design is even taught in physics and electronics classes anymore. ↩︎

- It’s also an early example of what became termed ‘faceless techno bollocks’ thirty years later. Then, the cult of the club DJ and the convenience of global electronic dance music ‘hits’, knocked out in bedrooms and understairs cupboards, combined to create a scene largely indifferent to authorship and authenticity, let alone fame and personalities. ↩︎

- This is a good point. Apart from George Martin already having done it with The White Suit Samba ten years earlier. The real question is: who else but George Martin would have thought of actually doing it and who else but the RWS would have the skills to make it a reality? ↩︎

- The Off The Record column written by ‘Disker’ would go on to play a part in The Beatles’ story. The Disker pseudonym was initially cover for Tony Barrow who started writing for the paper at age 17 – too young to be taken seriously. By 1962 he was working for Decca in London writing album sleeve notes whilst still turning in his weekly singles review column in the Echo. As a Liverpudlian, he did his bit promoting the Fab Four for EMI in the Echo, despite taking a wage from their rival label Decca. A further reason to use an alias in print. This was all in the future though and his interest in Ray Cathode was just in the line of duty. The Liverpool Echo had a circulation of around 1 million at this time including the Beatles themselves. This review would be more evidence for them of George Martin’s expertise. ↩︎

- Among her other accomplishments, Delia Derbyshire was out in front on this attempt to bring the worlds of tape-constructed music and pop songs together. That is another story though… ↩︎

- Release date per NME and Liverpool Echo from the week prior. ↩︎

- Thumb or finger rolling. I learned about this technique while trying to figure out what the heck was going on. ↩︎

- Meek had attempted ‘an outer space music fantasy’ in 1960 with I Hear A New World which was far stranger than Waltz in Orbit or Telstar. ↩︎

- In The First 25 Years, the recollection is that it “didn’t get a very high placing”. I found no mention in the official UK charts at all though. ↩︎

- Mark Lewisohn again. I assume he is basing this assertion on Parlophone paperwork – specifically the per-play radio royalties paid by the BBC. ↩︎

- Blip blip.. it’s Ray Cathode – Sunday Mercury, 22nd April 1962 ↩︎

- Record Review – The Chronicle and Courier, 27th April 1962 ↩︎

- Record Review: Around The Table – South Western Star, 27th April 1962 ↩︎

- Like an Ordinary Organ – Coventry Evening Telegraph, 8th May 1962 ↩︎

Leave a Reply